A year ago, Rodrigo Duterte was voted into power by a people desperate for change. Today, many of his promises ring hollow, his regime quickly descending towards tyranny.

Echoes of Marcosian rule reverberate in the city streets, in rural communities rising against corporate greed. Over 13,000 have been killed in a drug war that eschews due process and targets only the poor, the police enabled by generous state funding and a climate of impunity. Martial Law has also been declared in Mindanao, where peasants and indigenous people are being terrorized by the military. Meanwhile, oligarchs continue to strengthen their grip on power.

What can art and artists do, in the face of injustice and authoritarianism? Dissident Vicinities, an exhibit curated by University of the Philippines Fine Arts Prof. Lisa Ito-Tapang, lends space for the important conversation.

effigy production installation by UGATLahi Artist Collective

“This exhibit,” writes Prof. Ito-Tapang, “reflects on the questions: How are people’s struggles visualized within various localities and spheres? How do social movements, in turn, contribute to the visual culture of collective resistance?”

We find answers in its diverse collection of artworks, many of which drew upon prior initiatives of people’s organizations. Renan Ortiz fashioned an effigy of the President called Death’s Head from placards used in previous protests, and the weight of such slogans as “Fight Neoliberal Policies,” “Stop EJKs,” “Junk EDCA,” and “Resume Peace Talks” – mostly signed by the militant labor union Kilusang Mayo Uno – gives the piece more history, more meaning. There is also the six-panel mural Portraits of Peace by KARATULA, Tambisan sa Sining, and UGATLahi, which took the place of the effigy during last year’s SONA, responding to that moment’s call for an artwork that reveals the Left’s challenges to the self-styled socialist.

In both examples, we see how an active people’s movement creates conditions for prolific cultural production. The parliament of the streets yields a wide range of protest materials which Henrielle Pagkalingawan illustrates in her inventory Objects that Object. Moreover, a dynamic conceptualization and production process by an artist collective goes behind every effigy, as documented in UGATLahi’s installation.

Artists are tapped for awareness-raising efforts that encourage them to integrate with the people, learn about the situation, and communicate it in a form accessible to their audience – “from the masses, to the masses,” as Mao Tse-tung’s edict goes. A dialectical interplay between the artist and the issue ensues: her attempt to understand the subject and convey this understanding through her medium transforms herself – her primary instrument for art-making. She draws attention to the issue, whose further development should spark the creation of new art, if not new modes of engagement.

Third from the World Installation by Renz Lee

Armageddon by Federico 'BoyD' Dominguez

False Prophet by Iggy Rodriguez

paintings by Voltaire Guray

The great artist and card-carrying Communist Pablo Picasso once said, “No, painting is not made to decorate apartments. It’s an offensive and defensive weapon against the enemy.” Dissident Vicinities demonstrates not only art’s potency as a political weapon as argued by Picasso, but also the different ways this potency may be harnessed.

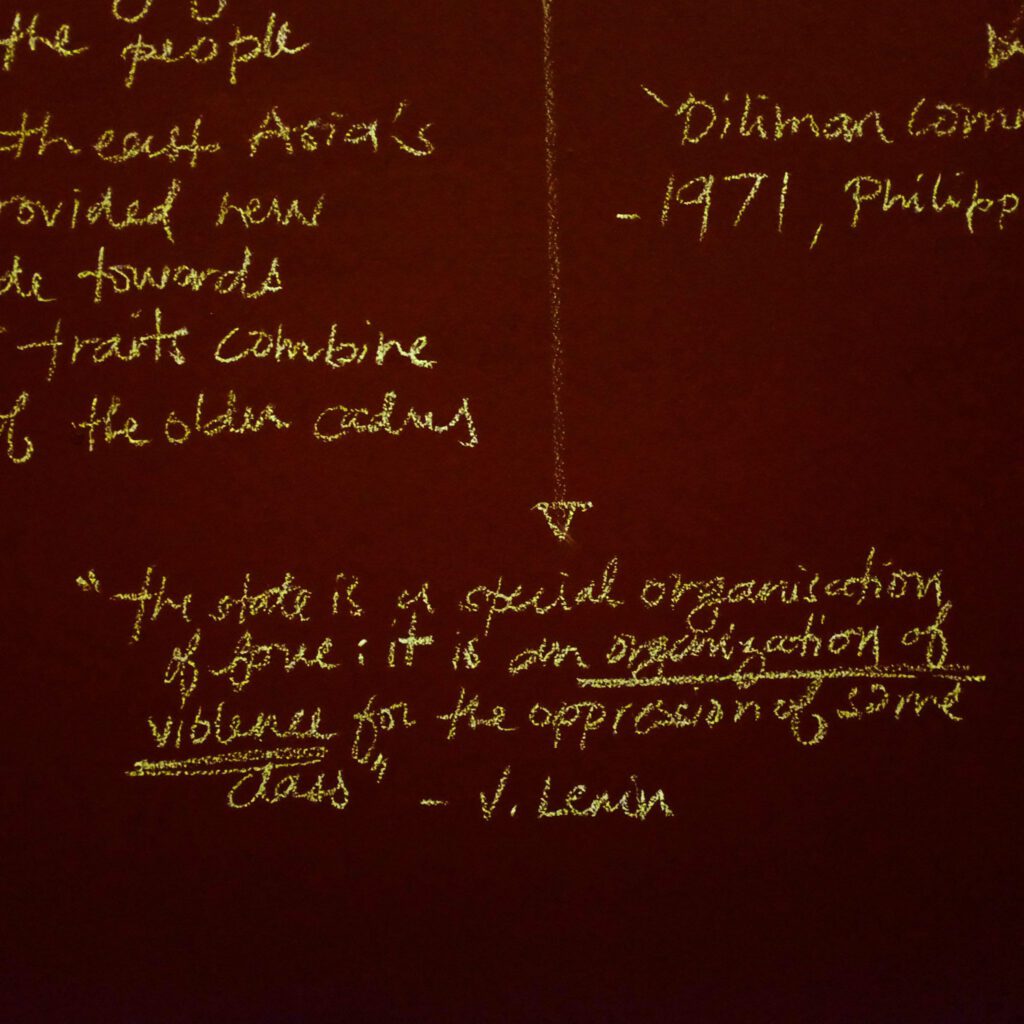

One is when art helps promote critical thought, as Renz Lee’s Third from the World installation, the piece that welcomes the exhibit-goers, does. A “lecture” delivered in chalk along with a few photos and illustrations, it tackles the Cold War-era political unrest in Southeast Asia, and urges the viewer to learn more about the relationship between and among such concepts as feudalism, capitalism, imperialism, and fascism.

Armageddon by Federico “BoyD” Dominguez accomplishes the same, his 2003 illustration on the casualties of the wars in the Middle East an invitation to pause and think about what the military-industrial complex includes and leaves out in its reportage. The artwork remains timely, too, as the US, NATO, and their allies continue to drop bombs on many countries in the guise of fighting terrorism. And now the list includes the Philippines, with the old city of Marawi being reduced to rubble by US-supported operations.

From critical thought comes the ability to challenge narratives of power, to dispute the established truths of the hegemony, and to seek possibilities for the reversal of its relationship with the subaltern. All these acts of dissent and dissidence can find space in art.

Effigy production, for example, places figures of authority at the mercy of the irreverent artist, who reduces them into necessarily unattractive caricatures, and then of the protesters, who decide the effigy’s fate. In the aforementioned work by Ortiz, Duterte is depicted as no more than the sum of his unfulfilled promises, while his eyes project onto the opposite screen the animated images of the chiefs of AFP and PNP. For is not the tough-talking leader the mere ambassador of their fascist agenda these days?

Meanwhile, in the painting Corporate Crusade/The False Prophet by Iggy Rodriguez, a man in coat and tie commandeers a tank, representing the impeccably dressed capitalist whose accumulation of wealth is premised on the dispossession of many.** Rodriguez strips this powerful capitalist of his humanity, and portrays him as a faceless creature, a mere cog in the neoliberal war machine.

Complementing the practice of challenging hegemonic narratives is telling the stories of the oppressed, which art also fosters. Many artists bear witness to injustice, using their pen, brush, or camera to speak of the plight of the marginalized. Pablo Baen Santos’ Internal Refugees mural does this for the bakwit of his time, his work – just like Dominguez’s – sadly as relevant today as it was in 1989. So does Nathalie Dagmang, whose poignant intermedia piece titled Mayflowers (Stories we only lean through Skype calls and letters) was inspired by her engagement with Filipino migrant workers trying to keep in touch with the affairs back home.

There is also Bihag, the haunting collaboration of painter and printmaker Prof. Neil Doloricon and graphic designer Tom Estrera, which captures the conditions of precarity that imprison the country’s toiling masses. Meanwhile, Archie Oclos’ Panginoong Walang Lupa, a piece that he installed at the Hacienda Luisita during Lent, speaks of the poor peasants’ decades-old struggle for land, for life.

But the principled artist takes care not to make a spectacle out of poverty, as most System-sanctioned efforts tend to. Instead, her work accords dignity to her subjects, and acknowledges their humanity and membership in the body politic. Such care is palpable in the video clip Mag-uuma by Kiri Dalena, where a woman not only sings of the sad, dirt-poor life of a peasant, but also enjoins her fellow poor to stand up for their rights.

When it is the oppressed themselves telling their stories through art, they may also find solace and healing. At the Bakwit School, for example, painting and drawing offer the Lumad youth a respite from the terror in their communities. Armed men, tanks, and helicopters dropping bombs appear in many of their works, along with handwritten pleas no child should have to make: Don’t bomb our school. Save our schools. Justice to our community leader. Stop Martial Law. Stop Lumad Killings. At the same time, they used art to express their hopes and dreams: they drew schools surrounded by flowers and trees, doves with olive branches, people joining hands, and a smiling sun rising from between the lush mountains.

Like them, Voltaire Guray found solace in art while in jail, his paintings revealing every political detainee’s desire for freedom. As grim and difficult incarceration might be, he drew hope from every opening, every chance to help free the world outside from the bigger prison.

An effigy by Renan Ortiz

Internal Refugees by Pablo Baen Santos

Panginoong Walang Lupa by Archie Oclos

drawings by Lumad students

portrait of Ka Parago by Aldrein Silanga

chlorophyll prints by Karl Castro

Finally, art realizes its political potential when it provides a language for showing alternatives to the current system, for exploring better ways to run the world. There is, for instance, another government that commands undeniable power in the Philippine countryside, the kind that breeds well-loved leaders like the late Leoncio “Ka Parago” Pitao of Southern Mindanao. Aldrein Silanga pays tribute to the slain New People’s Army commander by way of a large portrait, whose bright colors and solid figures capture the vigor of the resistance Ka Parago led.

More of the communities built around this resistance are depicted in Melvin Pollero’s exercise in ethnography called Buhay-Gerilya. Beautifully rendered using chalk on taffeta, it shows in detail the busy life in a guerrilla zone, where NPA members are engaged not only in warfare but also in farming, literacy promotion, health services, political education, and cultural work among the masses. The same guerrilla fighters figure in Karl Castro’s chlorophyll prints, just as in real life, they emerge quietly from the rustle of the leaves.

Both works negate the hegemon’s attempts to other the NPA. In Pollero’s, they also drink coffee, play the guitar, hang their garb on a clothesline, and take delight in carrying little children. In Castro’s, they do a lot of walking, their feet almost certainly just as calloused as everyman’s. Moreover, their works give us a glimpse of a fully-functioning society led not by rapacious landlords and capitalists, but by ordinary men and women united by an ideology.

Amid the worsening crisis and chaos of neoliberal capitalism, the ruling class – represented by the State – will expectedly try to stifle the voice of the resistance and destroy the people’s hopes for a new world order. It is then ever more important to create spaces for expressing rage against inequities, for imagining possibilities, for forging solidarities.

Dissident Vicinities succeeds greatly in this respect. May there be more of these initiatives to remind us of what is, what can and what should be.

—

*From Karl Castro’s Dissident Vicinities Artist’s Talk presentation

**As articulated by Marxist geographer David Harvey

Photos of artworks from the Dissident Vicinities Facebook account.